Why I wrote this

Since there’s no point hiding my EA-ness anymore, what with starting as Effective Altruism Finland’s Executive Director in September, it is time to take the cat out of the bag.

Why now? Why not before?

I am scared. I have been scared. I used to be too scared and imposter syndromed to properly apply for EA jobs. I fear there is a pull that value-aligned work has that heightens my changes of a bad burnout. Also combining a free time community with a job is scary.

My emotional motivations for EA have waxed and waned over the years. Due to life events, mental health, money, and social connections.

But when a person close to me died last January, I had to face some of my discomfort and stuck thoughts. Especially around the reality of death, and how bad, horrible and eternal it can be. And how many lights are lost from the world, every year, every month, and even every day.

After processing a lot of my sorrow, what was left was resolve. Anger, defiance, even recklessness. I don’t want to go on living more years while keeping altruism as a side project in my head. I want to channel this energy. And there is only one way to make death pay. Chip away at him. Make him stop.

I shall do my best.

Why do I strive to be an effective altruist?

Guiding light

I used to think that the guiding light for what is ethical to do with your life comes from a sense of guilt, duty, and “needing to do more”. I no longer agree with this.

Feelings like this can be motivators to introspect why you feel like you’re not doing enough, or why you are feeling guilty. But I don’t think they work as long term motivators as well as something more positive.

Replacing Guilt, a blog sequence about grounding motivation and action not in guilt and shoulds but in wanting to do things that aligns with your values, was an important read to me around 2020/2021, but I didn’t quite internalize the core lessons back then.

I have come to think it is especially important for me to cultivate a sense of hope, and positive future. The positive lightcone is where my motivation shines from, even when the world looks dark.

I trust in the value of the world and existence, even when times are hard and I have a hard time trusting myself.

State of the world

I have strong values. I feel an internal sense of rebellion over the state of the world. Millions, billions, even trillions of lifeforms die and suffer every year, and fail to have positive lives.

Trillions of dollars of resources are spent on zero-sum games keeping the wheels turning (military spending globally in 2024: \$2.718 Trillion), and only billions ($212 billion in 2024 according to OECD) on doing good.

I have not really believed in strong forms of egalitarianism since my teenage years. I do not think the core problem in the world is that resources need to be spent equally, relative to some measure.

But I do think it feels wretched how much surplus the richest 10 or 20 of countries have economically compared to the least well off 50%. Spending something like 5-10% in foreign aid feels to me like it should obviously be the long term goal for rich countries.[TODO: footnotes support: 1]

But then, my answer here is not that we should aim for less surplus. We should grow it, grow it much more, grow it ethically, and allocate it well. We should strive to build a world economy that serves each human and each animal to a good degree.

That was a bit of a rant. Let’s get back to values.

Felt sense of right

I have a really hard time splitting each of these between being an internally felt core value, and being a rationalization of some kind. Let’s try anyway.

Things I feel clearly matter:

- I have been granted the gift of existence, by the universe and all that humanity did before I was born. I feel it is only fair for me to want to pay this back.

- I do not feel like people have a duty to give to altruist purposes from their necessary resources but I feel like people have a duty to give from their surplus. (The line between surplus and necessary resources is hazy at best.)

- There is so much good that could be done in the world with just a bit more resources for good purposes. Instead resources are spent on zero-sum-games, suboptimal policy and the tenth thousandth high budget Hollywood movie.

- For what it’s worth, I think humanitys talent for creating new art is something to embrace, and not smother. But allocating resources to new art is different from producing the tenth thousandth-and-first Hollywood movie.

- There are large amounts of existing beings who could have significantly better lives.

- I think there are large amounts of beings who do not yet exist but could have decent-to-excellent lives.

- I do not believe closeness or species defines who deserves compassion and moral patienthood.

- I think there are huge open questions in ethics, governance, and how to make the world good, and it is important to strive to answer these eventually.

What to do then?

So since it seems clear that some good should be done, and that I have surplus and personal reasons to do some good, what to do then?

I think there exists a simpler case, and a complicated case for Effective Altruism. Let’s explore both:

Simpler case:

You already know some outputs you want to achieve, or where you want to focus your aid, and you are deciding what specific intervention or organization will best achieve your desired outcome.

- If you live in a 1st world country and you want to help the global south, and do not have very deep knowledge about specific interventions, it seems clearly better to help effectively than to help ineffectively.

- So if your options are “donate \$30 to a Unicef program to aid a single family in the global south for an immeasurable amount” or “donate \$30 to Against Malaria Foundation to get 15 long-lasting insecticidal nets to save 0.55% of a life in expectation”, I think the second clearly wins.

- (Not just based on vibes but - there are measurement programs like Givewell that say that Against Malaria Foundations numbers are good.)

- So if your options are “donate \$30 to a Unicef program to aid a single family in the global south for an immeasurable amount” or “donate \$30 to Against Malaria Foundation to get 15 long-lasting insecticidal nets to save 0.55% of a life in expectation”, I think the second clearly wins.

Counterarguments:

- “But what if the \$30 dollar donation does something really important for the family and manages to say save an entire life there?”

- Of course outcomes in the real world are not always predictable. However I think there is a strong case for probabilistic reasoning

- When outcomes are uncertain we should measure the change that something good happens, and the amount of that good, and work on the expected good done. I don’t have a large philosophical reason for this, there just seems to be no better model for reasoning about uncertain outputs in the real world.

- Absence of evidence is evidence of absence

- Unicef is a huge non-profit organization, and if they could show quantifiable numbers of their output, they most likely would.

- It is suboptimal to reward actors in the real world for keeping their outputs and estimations fuzzy

- Therefore we should demand rigorous estimates.

- Humans have a bias to disprefer known downsides

- It is easier to hope and believe that the Unicef donation will do something great.

- But this is not a substantive argument that it will.

- It is easier to hope and believe that the Unicef donation will do something great.

If you want to help with climate change it seems obvious that an effective intervention is better than a non-effective one.

For more information on this subject see givewell.org, thelifeyoucansave.org, or in Finnish lahjoittaminen.fi

Complicated case:

If you do not already know what outputs you are looking for, just that you want to help somehow, then we need to get more philosphical.

The classic thesis of Effective Altruism is that you should help the world, if you can afford to, and you should try to do it effectively.

And you buy this thesis but you do not know what you want to help with.

From an altruistic perspective, the world is filled with terrible badness. People living in dictatorships, climate change, hunger, illness, factory farming, death, war, risks of nuclear war, pandemics, and at the end (or start) of the list many Effective Altruist sources give you, even existential risk from advanced artifical intelligence.

How to decide between these?

- You need to reflect on your values. How do you value humans, compared to mammals, compared to insects.

- You need to reflect on how to estimate outcomes in the real world. Do you accept simple expected value reasoning, such that a plan with a 1% change to save a 100 people is worth the same as a plan with 100% change to save 1 person? Do you take this to it’s natural conclusion?

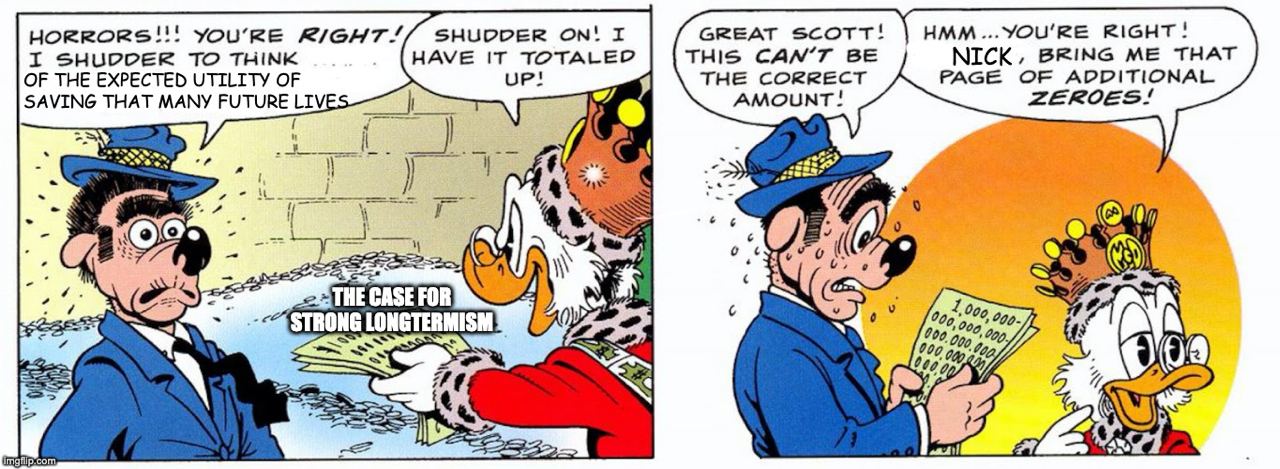

Sometimes reasoning like this can lead to conclusions that go quite far. Even if you take a time discounting function (as defined by economics) of a few % a year to deal with uncertainty, if there are say 10^58 possible future lives (as estimated by philosophers and cosmologists) this can still mean that the in moral worth the next few thousand years are only a blink of the eye in the scale of all of future. (And many moral philosophers think there is a case against time discounting for moral value.)

(TODO: tarkista numero)

Even if you don’t believe that lives are exchangeable or anything like that, I still think the number is important to consider. I think a common counterargument is that “But these are real people! We cannot just do math on their lives!“. But all the other lives we could aid are also real people - if we don’t do any evaluation and just put our head in the sand, we are leaving some of the decisionmaking process off to random change.

To me the core thesis here is not saying we should only do math to define how one should help. The thesis is that if you do not do any math, no quantitative reasoning, you are leaving information on the table and that leads to suboptimal decisions. You should do the math, and then you can decide how to weigh the math and other relevant factors.

Waryness

I think people have a tendency to be wary of large answers to simple philosophical reflections. I think in some degree this is healthy - often when you have an emotional feeling like “this is lifechanging and I must change what I am doing to act on it” it could be something worthless or dangerous - like a cult or other entity trying to pull on your strings.

But this is only a protective heuristic, and sometimes the real world truly is so complicated, and we truly have enough new evidence, that we need to do drastic changes.

But I think if you feel the call of altruism, and the pull to answer, you should not be too hasty to put it back into the box.

Back to the personal

I personally feel like there is a cost with focusing too much on the far future. But I also feel like the average citizen of the world is way too disconnected from the future that awaits us.

Emotionally, if I take a moment to reflect, I can quite easily imagine the people of the future yelling at us, telling us to acknowledge the fact that they matter. And I do not have the heart to tell them no.

(Also, on a more rational level - opportunity costs are real costs. If humanity does “decently” by some metric, but misses out on 95% of possible future value, we have lost that 95% forever. In the real world there are no excuses.)

I personally find it intuitive that the preferences of not-yet-existent or even not-going-to-exist moral patients, but who could be made exist, matter.

This leads me to conclude that we have a clear need to consider the preferences and worth of future humans, animals, and other moral patients.

The beings of the future are calling for us, and I, hearing their call, will do my best to answer

Footnotes

- I don’t know what an economical model of high foreign aid would actually yield as long term consequences. But that is also why I framed this as a feeling instead of a stabler policy position.